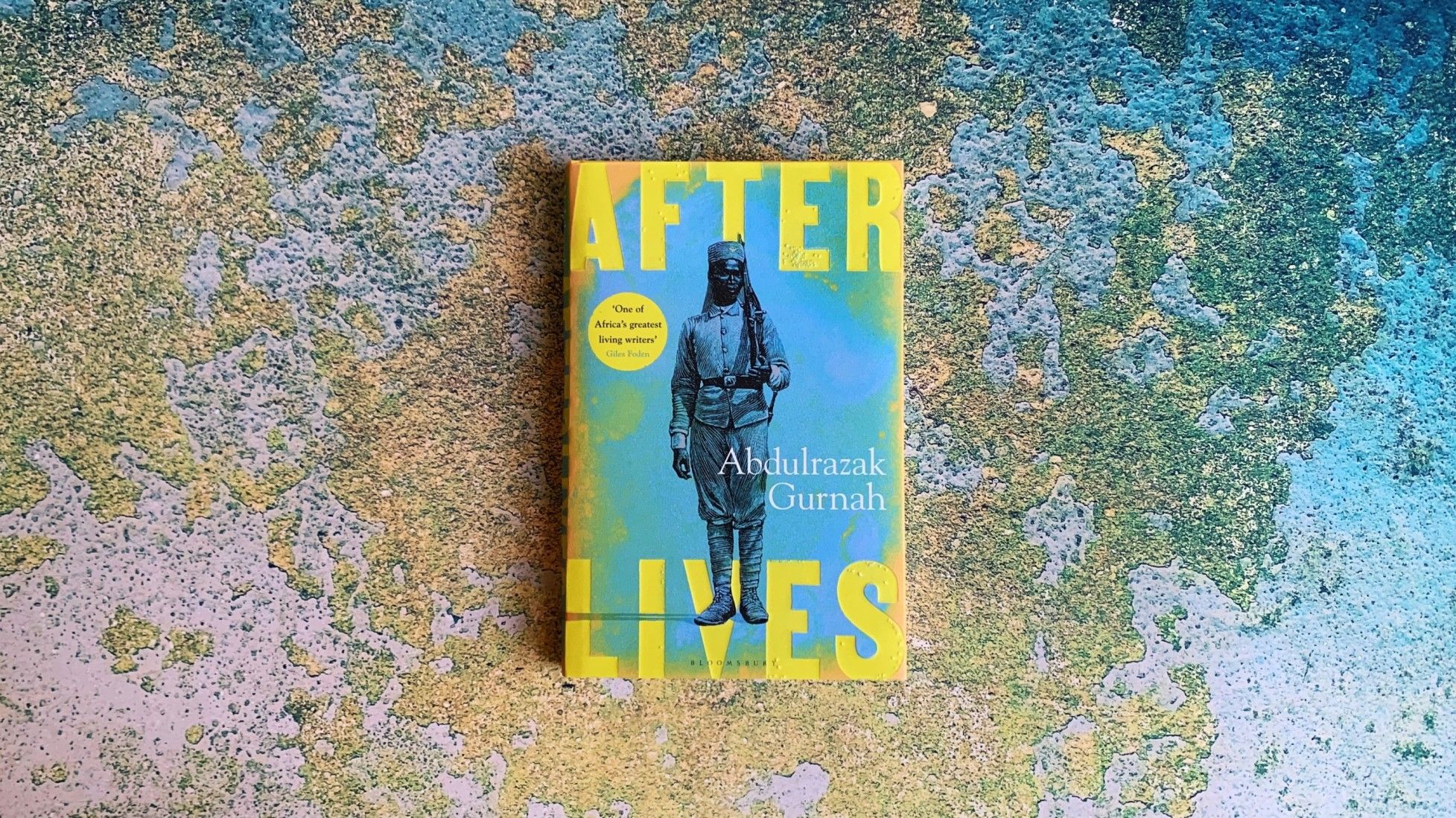

看完了「Afterlives」

The book, writes Financial Times, “tells the story of four main characters whose lives intersect with each other in love and kinship, and which are moulded by great forces beyond their control, principally the colonial tussle over the land they inhabit.”

- 看了才知道坦桑尼亚这个国家是怎么组成的;

- 翻译应该很困难吧。又有非洲语,德语,混杂英语的;

- 印度人在非洲也是一个seafaring 的种族

- 看这本书有种看大江东去,平凡的世界的感觉,就是平平淡淡地讲几个人在那个时代的故事,不经意间就把整个历史的context都交代清楚了。

- 看到64%,Ilyas出现后就消失了;我一直觉得Hamza会和Afiya发生些什么连接;书名Afterlives,我到现在还没法发现端倪。

- 76%,Ilyas还未出现了,Afiya都要结婚了。

- 当小朋友Ilyas开始自言自语时候,这时才有种afterlives的感觉。书已经接近尾声了。所以说作者能拿诺贝尔奖,叙述能力是超强的。这么说吧,我在看这段英文的时候,能够让我感觉毛骨悚然,在这么一本平和的,如同平凡的世界的小说上,手臂感觉会起鸡皮疙瘩的感觉。怎么地,是要往鬼片方向描述吗?这事,后续不了了之,小朋友长大后就好了。

- 这本书里每个人物都是善良的,看下来就不会让人不舒服。战时,你在英国殖民地收到一封德国的来信,也只是警察简单的询问,挥挥手就让你回了。这要是放在中国的编剧里,能做的文章,可做的文章太多了。但是我还是喜欢作者的选择和处理手法。我比较喜欢书里Khalifa这个角色,他是唯一清醒的人,斥责迷信,反战,教书育人,除了嘴碎点,愿意帮助人,可以把第一天认识的人就带回家里,找个房间给他住。

- 小Ilyas长大了,获得了教育,也有机会到德国去寻找自己的伯伯。书在最后部分写了Khalifa和Bi Asha的离去,人都是无法避免死亡的,在那个年代能活到五十多,六十多也算是幸运了,书里的金手指感觉是开给了Kahlifa,就是有一双洞穿人心,社会的眼睛,所有的点评都是地道直接的。当然,也有马失前蹄的,比如他大伯就看错了。大伯出场还是生猛的,一开始就会说德语,到城镇里面就直接能在德国人的公司里找到工作。十二岁时候自己一个人毫无来由地就离家出走,后来被Askari收留,之后又被教会学校收留,学会了德语。成年后也是很厉害的,想起了自己有妹妹,穿一身西服就过去把妹妹接出来了。之后就是开始天花乱坠了,要去参军,把妹妹又送回虎窟;参军之后一去不复返。我看着书,还一直幻想着他们全家能重逢,一直到最后都没有。他们的大伯一个黑人,最后在德国加入了纳粹,一直叫嚣着光复德国在非洲的殖民地;最后和他的孩子一起1943年死在了集中营。这个反转意料之外,但也是情理之中。给作者点个赞。

Afterlives (Abdulrazak Gurnah)

caravan

Several months passed before they received a reply, and only did so because the tutor went round to plead with the brothers, for the sake of his reputation.

The brothers Hashim and Gulab were moneylenders, which as they explained to Khalifa is what all bankers really are.

For Khalifa, the modesty of the bribe allowed him to suppress any feeling of guilt at betraying his employers. He told himself he was acquiring experience in business, which was also about knowing its crooked ways.

His secretiveness and ruthlessness in business were thought essential qualities in a merchant.

‘It just came on me a few months ago, this weakness,’ he told Khalifa. ‘I thought I would go first, but your mother beat me to it. She shut her eyes and went to sleep and was gone. Now what am I supposed to do?’

Khalifa left him and went out to the back for a wash and to boil water for their tea. Then as he stood waiting for the water to boil he felt a shiver of dread and went back inside to find that his father was not sleeping but dead. Khalifa stood for a while looking at him, so thin and shrunken in death when he had been so vigorous and such a champion in life.

When he returned to town and for several months afterwards Khalifa felt alone in the world, an ungrateful and worthless son. The feeling was unexpected. He had lived away from his parents for most of his life, the years with the tutor, then with the banker brothers and then with the merchant, and had felt no remorse for his neglect of them. Their sudden passing seemed a catastrophe, a judgement on him. He was living a useless life in a town that was not his home, in a country that seemed to be constantly at war, with reports of yet another uprising in the south and west.

The house was the property Asha Fuadi inherited, only she did not inherit it.

reticent

She knew her own mind, often if not every time, and once she did she was firm whereas he was easily swayed by words, sometimes his own.

Asha shivered and trembled with increasing intensity until finally she burst out in incomprehensible words and sounds. Her outburst reached a climax with a yell and then she spoke lucidly but in a strange voice, saying: I will leave this woman if her husband makes a promise to take her on the hajj, to go to the mosque regularly and to give up taking snuff. The

When it’s your time, it’s your time.

His creditors came along in due course with their paperwork in good order. Those who owed him kept their heads down and the old merchant’s fortune was suddenly a lot smaller than had been rumoured.

Ilyas smiled and protested and bantered back.

It did not hurt very much and other things made her feel more sad, made her feel small and a stranger in this world. Other children were also beaten every day.

They talked together for some time before they called for her to come in. Her brother gestured for her to sit while he explained that she was to come and live with him in the town. She was to gather her things and be ready to leave with him in a short while. She collected her little bundle and was ready within minutes. Her aunt watched her closely. Just like that, not even thank you, goodbye, she said reproachfully. Thank you, goodbye, Afiya said, ashamed of her own haste.

She did not even know she had a real brother. She could not believe he was here, that he had just walked in off the road and was waiting to take her away. He was so clean and beautiful, and he laughed so easily. He told her afterwards that he was angry with her uncle and aunt but he did not show it because it would have seemed that he was being ungrateful when they had taken her in although she was not a relative. They had taken her in, that was not nothing. He gave them some money as a gift for their kindness but he did not need to, because she was in filthy rags when he found her as if she was their slave. ‘If anything they should have paid you for having made you work for them like that for so long,’ he said. It did not feel like that to her at the time, only afterwards, after she started living with him.

‘I ran away from home while Ma was pregnant with you. I don’t know if I really meant to run away. I don’t think I did. I was only eleven. Our Ma and Ba were very poor. Everyone was poor. I don’t know how they lived, how they survived. Ba had sugar and was unwell and could not work.

I am not saying this to be unkind but to explain to you that perhaps these were the things that made me want to run away.

Everything was a little worse than before and it hurt more.

She warned herself to put up with it because her brother said to do so until he came back for good.

‘I hear you have learned to write. I don’t have to ask who has taught you to do this. I know exactly who it is – someone with no sense of responsibility. No, someone with no sense at all. Why does a girl need to write? So she can write to a pimp?’

‘You should be ashamed of yourself. Everybody in the village heard him shouting and beating the child. It’s as if he is out of his mind.’ ‘He did not mean to hurt her like this. It was an accident,’ her aunt said.

For a long time Afiya did not like to go anywhere in case they came looking for her. She was afraid of everyone except for her brother’s friend who had come for her and whom she was now to call Baba Khalifa, and Bi Asha, who fed her wheat porridge and fish soup to build her strength, whom she was now to call Bimkubwa. She was sure that if her Baba had not come, her uncle would have killed her sooner or later, or if not him then his son. But Baba Khalifa came.

The recruits were on the march with varying degrees of consent: some were volunteers, others were volunteered by their elders who themselves were under duress, some swept up or coerced by circumstances, some picked up on the road.

One of them broke into song, his voice deep and gloaming, and some others who knew his language took it up with him.

but he was ignorant of what he had now sold himself to, and of whether he was up to what it would demand of him.

swine

Even when he was silent, he struggled to contain his exasperation.

he expected the ombasha, who was present at all the sessions, to step in with blows when his words needed emphasising.

To Hamza it seemed a cruel caprice to no purpose but it was too late for such wisdom and there was nothing else to do but endure.

He did not know if being a signalman was any safer than being an askari but it was not the moment to quibble.

‘Only I don’t think you will ever learn mathematics. It requires a mental discipline you people are not capable of. That’s enough for now,’

By then Hamza was silently cringing with humiliation and fearful that their predictions of what was to befall him would turn out to be true.

By then Hamza was silently cringing with humiliation and fearful that their predictions of what was to befall him would turn out to be true. He had felt himself one of them, had shared their privations and punishments, and no one among them had spoken to him in such a slighting way before. It was as if they were forcibly expelling him from their midst.

Bi Asha prayed for her and taught her to read the Koran. If we read together then you will not be thinking so much about your pain and God will bless you and reward you, she said.

The merchant spoke just as sharply. ‘Leave her alone,’ he said, and then she understood that he disliked Baba Khalifa just as much as Baba disliked him.

A new bed with a mosquito-net frame was delivered from Nassor Biashara’s workshop as a gift to Afiya from the merchant. The mattress-maker came and unstitched the worn-out mattress she slept on on the floor and filled it with new kapok. A new net was ordered from the tailor and hung glowing white in its frame. For the first time in her life, at the age of twelve, Afiya had the unexpected luxury of a room of her own.

‘You don’t know how lucky you are,’ Bi Asha told her, but she was smiling, not scolding. ‘I hope we are not spoiling you with all these comforts.’

She thought it embarrassed him the way they looked at her. She knew what was happening without anyone explaining it to her, and she accepted the kanga gratefully and covered herself as she was told.

veranda

sardonic

For one thing, the askari would not go to war without their partners. For another, the schutztruppe lived off the land when they could and it was the women who foraged for food and information, who cooked for the troops, traded where there was trade, and kept their husbands content. It was a concession Wissman had to make when he set up the schutztruppe and it was not possible to unmake it without risking widespread mutiny and desertion.

Later these events would be turned into stories of absurd and nonchalant heroics, a sideshow to the great tragedies in Europe, but for those who lived through it, this was a time when their land was soaked in blood and littered with corpses.

The officers made every effort to meet for a mess dinner every evening, where etiquette was observed as far as possible. They did not do any of the physical work associated with the askari or carriers: transporting equipment, foraging, making camp, cooking, cleaning dishes. They kept their distance, eating separately, demanding deference wherever they could.

He was in a state of terror from the moment he opened his eyes at first light, but in his exhaustion he sometimes reached a stage when he was unafraid, without bravado, without posturing, detached from the moment and open to whatever might happen to him. Sometimes he lapsed into despair.

There was still some haggling to do, but despite arguments back and forth that was how it ended up. Throughout the remaining years of the blockade, Rashid Maulidi brought in small supplies of whatever he could purchase in Pemba and Khalifa hid them away in the warehouse where trusted traders came to do business. It was not riches but it kept the business going and allowed Khalifa to find a new role for himself as a trader in contraband as well as a warehouse keeper. He dealt with Nassor Biashara politely, if at times irritably, and they largely left each other alone.

Whenever Afiya made ready to go out, Bi Asha asked her to say where she was going and what she was going there for. When she returned, Bi Asha asked for an account of who she had seen and what was said. By degrees, without even realising what she was doing at first, Afiya found herself asking Bi Asha’s permission before she went out. Bi Asha commented on what she wore, commending or reproving as seemed appropriate to her. The

Afiya was sure that Bi Asha searched her room when she was out. She was by now resentful and guilty at the same time because she reminded herself of the kindness Bi Asha had showed her when she was a wounded and frightened child.

If Hamza did not have anything to say, he repeated the last thing the officer had said.

consternation

spasms

‘Oberleutnant like you, that’s why you lucky. Otherwise we throw you away in the forest, hamal.’

recuperate

nuisance

seepage.

unadorned

‘It is a place of no significance whatsoever in the history of human achievement or endeavour. You could tear this page out of human history and it would not make a difference to anything.

That was how he so unexpectedly came to work for the merchant Nassor Biashara. The merchant later told Hamza that he took him on because he liked the look of him. Hamza was then twenty-four years old, without money and without anywhere to stay, in a town he once lived in but knew very little of, tired and in some pain, and he could not imagine what the merchant could like about the look of him.

Hamza had been ashamed to ask, in case the merchant refused or withdrew his offer of a job. He had not even asked what his wages were to be.

It made Hamza take another look at Khalifa, this generous offer, the coin earlier in the day, all that kindness alongside his irritable manner and sour looks. I like the look of you, he had said. Nassor Biashara had said that to him too. It had happened to Hamza before, that his appearance had won kindnesses for him in unexpected ways. The German officer had said that too, more than once.

Look like Kobe Bryant?

He shut the door and sat for a long time, for hours, without moving, relishing the feeling of safety he felt in the darkening cell.

In so many places he had travelled there were no mosques, and he missed them, not for the prayers but for the sense of being one of many that he always felt in a mosque.

‘Hey, you kafir,’ Topasi said. ‘Don’t discourage a man from saying his prayers. You are making even more trouble for yourself. You’ll earn a bucket-load of sins for that and you already have a huge pile against your name.’ ‘Never come between God and man,’ Maalim Abdalla pronounced.

struggle but on others he saw torn and mutilated

mutilated

By this time the nahodha and the mechanic were talking and laughing together in self-congratulation as if they had known each other all their lives, which they very likely had.

blasphemers,

It was still an improvement to be obliged to be useful rather than to be greeted as an impending disaster: Balaa. Hana maana. *

weasel

reticent.

He tried to maintain a line between being a servant, which he did not wish to be, and a dependant who had obligations to the household but who made no presumptions.

‘Leuchtturm Sicherheitszündhölzer.’ Hamza found the box of matches tucked away in one of the drawers in the workshop and read the brand name out loud. Mzee Sulemani looked up enquiringly from his sanding, ‘What did you say?’ he asked. Hamza repeated the words, Leuchtturm Sicherheitszündhölzer. Lighthouse Safety Matches. The old carpenter moved over to where Hamza stood and took the matches from him. He looked at the box for a moment and then handed it back. He walked to a shelf and took down a tin which they used for nails that needed straightening. He brought that over to Hamza who read, ‘Wagener-Weber Kindermehl.’ ‘You can read,’ the carpenter said. ‘Yes, and write,’ Hamza said. He could not keep the pride out of his voice. ‘In German,’ the carpenter said. Then pointing to the tin, he asked, ‘What does that say? ‘Wagener-Weber Baby-milk.’ ‘Can you also speak German?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘Mashaalah,’ Mzee Sulemani said.

Indeed an elation moment

‘It’s getting better,’ he said. ‘Thank you.’ The moment was coming when what needed to be said would be said but she was not sure if she should press matters forward or wait for him to act. She did not want him to think she knew how to do such things, for him to think that she had done such things before. She wished she could confide in Jamila and Saada, and many times the words were on the tip of her tongue but something held her back. She wondered if it was from fear that they would mock him and tell her to come to her senses and not act in such a self-disregarding way with a man whose people she did not know. Perhaps they would think him a penniless wanderer, not that she was anything more than that herself. She was a woman, they would say, and in the end all a woman had was her honour and was she sure he deserved the risk? She did not dare mention him to Khalida either, because she would only tell her friends who would howl with laughter and encourage Afiya to audacities she was not really up to. Anyway, what was the rush? She did not feel impatient and even liked the tense anticipation of fulfilment. At other times she was afraid she would lose him, and he would move on as he had come, heading nowhere in particular but away from her. She had understood that much about him, from looking and listening, that he was a man who was dangling, uprooted, likely to come loose. Or at least that was what she guessed from what she saw, that he was too diffident to make the decisive move, that one day she would wait for him to come to the door for the bread money and he would not appear and would be gone from her life for ever. It was a fear that filled her with dejection, and at those moments she was determined to give him a sign. Then the moment would pass and she would be back with her own caution and uncertainty.

From overheard conversations he could put names to some people and even learned brief histories of them, although those could well be exaggerations prompted by the café ambience.

He loved looking at the waves from here, just gazing for a while, following the line of the surf with his eyes, watching it come in with a muted roar and then retreat with an impatient hiss.

He had not been forced to go as a child and now it gave him pleasure to make his own choices.

stoicism

‘They treated her like a slave. Has she told you that? The man she called her uncle beat her with a stick and broke her hand. When he did that she sent me a note – yes, that’s right. Ilyas taught her to read and write, and I told her if she was in trouble she was to write a note addressed to me and give it to the shopkeeper in the village. That’s what she did, the brave little thing. She wrote a note and the shopkeeper gave it to a cart driver who brought it to me. So I went and got her and she has lived here for the last eight years. It will do her good to make her own life now,’ Khalifa said. ‘Have you spoken to her?’

‘That makes me happy,’ Khalifa said. ‘You must tell me more about your people, your lineage. What are the names of your father and mother, and what are the names of their mothers and fathers? You can tell me this later. I have seen enough of you to be reassured but I promised Ilyas. I feel a responsibility. Poor Ilyas, his life was attended with difficulties yet he lived under a kind of illusion that nothing bad could ever happen to him on this earth. The reality was that he was always on the point of stumbling. You could not imagine someone more generous nor anyone more self-deluded than Ilyas.’

Hamza had begun to think of Khalifa as a sentimental bearer of crimes, someone who took a share of responsibility for other people’s troubles and for wrongs done in his time: Bi Asha, Ilyas, Afiya and now Hamza, people he quietly cared about while disguising this unexpected concern with outspoken brashness and persistent cynicism.

‘You are too good for this world, my one and only. Don’t be ashamed, hate him, wish ill on him, spit on him.’

‘What can we find out? Maybe this way I don’t have to know for sure, and what happened has happened. If he is well somewhere, my knowing does not make any difference to him, and if he is well somewhere, perhaps he does not want to be found,’ she said. ‘I must go.’

‘But listen to what I am saying: good fortune is never permanent. You cannot always be sure how long the good moments will last or when they will come again. Life is full of regrets, and you have to recognise the good moments and be thankful for them and act with conviction. Take your chances. I am not blind. I have been looking and I have seen what I have seen and I have understood, and some of what I have seen has made me anxious. I thought I would wait until you were ready to speak to me, that I would not rush you or embarrass you, and that in the meantime nothing unseemly would happen. Now that Ramadhan is over and all the holiness is behind us, now that Idd has arrived and a new year has begun, it may also be the time for you to show some conviction. If you wait too long you may lose the moment or else be drawn into something regrettable. So I am giving you a little nudge.

‘Yes, I know I said you should just lie but this is different. This is not something to joke about, this is not about keeping the peace and moving things along. Perhaps you think I am being a meddlesome patriarch, interfering in the way a young woman might choose to live her life. I am not her father or her brother but she has lived with us since she was a child and I have a responsibility to her. It is important that we know about you so our minds can be at rest. You don’t have anywhere to live, and it is likely you will continue to live here with us. I would like you to continue to live here with us, so that too is another reason we need to know more about you. You could be anybody. Of course, I don’t believe for one minute that you did something bad before you came here, or no worse than the rest of us have, but I need you to tell me that. Look me in the eye and tell me. If you tell me a lie about yourself, I’ll see it in your eyes.’

Khalifa sighed at this new detail, which was now going to make his story so impossibly rich that no one would believe it. ‘So that’s who you are,’ he said. ‘I was here working

Khalifa sighed at this new detail, which was now going to make his story so impossibly rich that no one would believe

Khalifa sighed at this new detail, which was now going to make his story so impossibly rich that no one would believe it.

That was when he asked her. He had told Khalifa that he would ask her himself, because he wanted her to say that it was something she wanted too. Khalifa said that was not how things were done. He, Hamza, should speak to Khalifa who would speak to Bi Asha who would ask Afiya. Then her reply would travel back the same route. That was how things were done, and that was how things will still be done after Hamza had spoken to her, but if he wanted to ask her himself as well, he should go ahead and ask.

‘I have nothing,’ he said. ‘Nor do I,’ she said. ‘We’ll have nothing together.’ ‘We won’t have anywhere to live, just this store room without even a mosquito net. We should wait until I can afford to rent somewhere more fitting,’ he said. ‘I don’t want to wait,’ she said. ‘I did not think I would find someone to love. I thought someone would come for me and I would have no choice. Now you have come and I don’t want to wait.’ ‘There is nowhere to wash. Only the mat to sleep on. You will live like an animal in a burrow,’ he said. She laughed. ‘Don’t exaggerate,’ she said. ‘We can wash and cook inside, and make love on the floor whenever we want. It will be like a journey together and we will find our way even if our bodies smell of old sweat. She has been wanting me to go for years.

That was when she first came out with it. She accused him of that, for many days. When he brought you that day, when he brought you inside, I think he wanted me to see you. I don’t know if he really meant to do that, maybe he just liked you. But I saw you, and each time I saw you I felt a little more longing for you. I didn’t know it would be like that. That’s why I don’t want to wait, and why this room is not a burrow.’

The couple married fourteen days later.

‘Maybe you will write one day,’ she said. ‘Maybe you will be able to forget that terrible time one day even if you don’t forget her. Sometimes when I am away from the house I think I will come home and find that you are gone, that you have left me and disappeared without a word. I don’t know if I understand everything about you yet and I am so terrified that I will lose you one day. I lost my mother and father before I even knew them. I don’t know for sure if I remember them. Then I lost my brother Ilyas who appeared like a blessing in my childhood. I could not bear to lose you too.’ ‘I will never leave you,’ Hamza said. ‘I too lost my parents when I was a child. I lost my home and very nearly my life in my blind desire to escape. It was not much of a life until I came here and met you. I will never leave you.’ ‘Promise me,’ she said, stroking him and signalling her

‘Maybe you will write one day,’ she said. ‘Maybe you will be able to forget that terrible time one day even if you don’t forget her. Sometimes when I am away from the house I think I will come home and find that you are gone, that you have left me and disappeared without a word. I don’t know if I understand everything about you yet and I am so terrified that I will lose you one day. I lost my mother and father before I even knew them. I don’t know for sure if I remember them. Then I lost my brother Ilyas who appeared like a blessing in my childhood. I could not bear to lose you too.’ ‘I will never leave you,’ Hamza said. ‘I too lost my parents when I was a child. I lost my home and very nearly my life in my blind desire to escape. It was not much of a life until I came here and met you. I will never leave you.’

She remained still throughout, slowly becoming resigned to the loss.

It was as much to fill the empty hours after the daily household chores as for the money that they did it, gladly doing something that engaged them and required skill, to ease the frustration of the hemmed-in lives they were forced to endure.

She kissed Bi Asha’s hand as she lay in her bed and sat on a stool beside her, making the kind of conversation people did by a sickbed.

They called the baby Ilyas.

Later that afternoon, without coming awake once since the baby’s arrival, Bi Asha passed away in unaccustomed silence.

‘It is so final, that is what is surprising, what I did not properly understand,’ he said, ‘that this person is gone forever.’

‘Unless you believe the fairy story that all the dead will one day come back to life?’

‘You’re turning into a conniving little manipulator! First you charm that old grumbler so that he takes you into his house, then you seduce his daughter and bamboozle the old carpenter with your German translations, and now you are trying to blackmail me,’ Nassor Biashara said. ‘I told you, I’ll think about it.’

There was still no word from or about him. It was now six years since the end of the war and it caused Afiya much anguish that she could not decide whether to give up hope and grieve or keep thinking of him as alive and on his way home. After all, she lost him for nearly ten years once before and then he turned up like a miracle.

He was busy being a grandfather.

It seemed to Hamza that this silence was a place in which his son found refuge.

It seemed that bad times never left them for long.

When she told Hamza he was enthusiastic. You fit all the requirements, he said. There is such a need for it, and you yourself will learn new skills.

‘If he’s still alive.’ Hamza regretted the words as soon as he said them.

They did not talk much, that was not their way, but sometimes Ilyas held his father’s hand as they walked.

‘What voice? What voice?’ Afiya said in alarm, knowing they were back in trouble again when she had thought they were safe. ‘It’s the woman. I can’t make her stop.’

He was calling out his name, Ilyas, Ilyas, but in a woman’s voice. Hamza climbed into bed with him and held him in his arms while he struggled.

Khalifa said to Afiya, ‘He is asking for your brother Ilyas. I knew it was a mistake to call him that. All this war talk has brought it back. Maybe he is blaming himself. Or you. Maybe that’s why he speaks in a woman’s voice. He is speaking for you. There is no one here who can help him. If you take him to the hospital they will ship him to an asylum a hundred miles from here and put him in chains. We have to look after him ourselves.’

The signs did not abate even after repeated doses of dissolved holy words.

Hamza had thought of writing to her before to ask if there was a way of finding out about Ilyas from the records in Germany. He was discouraged by the audacity of the idea. Why would she bother to find out? How would she know about the records of the schutztruppe askari? Who cared what happened to a lost schutztruppe? In addition, he was discouraged by his own lack of a return postal address.

Both the front door and the window were closed, so all they saw were three elderly men sitting on the porch pretending that nothing unusual was happening inside.

He had been talking about joining up for more than a year but Khalifa so vociferously opposed this move that Ilyas did not dare disobey. This is nothing to do with you, he said to Ilyas. Isn’t it enough that your father and your uncle were stupid enough to risk their lives for these vainglorious warmongers?

He did not take part in any fighting but he learned a great deal about the British and their pursuits. He also learned to ride a motorcycle and drive a Jeep, and even to tinker successfully with its engine. He played football and tennis and went fishing with a speargun and flippers. For a while he even smoked a pipe.

He asked about his uncle Ilyas, if they had any more news. He always asked, not expecting any.

In 1963, two years after Independence, which both his parents lived to see, Ilyas was awarded a scholarship by the Federal Republic of Germany to spend a year in Bonn learning advanced broadcasting techniques.

The African man in schutztruppe uniform was named as Elias Essen.

He asked the archivist for a copy of the original and sent it to his mother. She replied in a few days to say it was his uncle Ilyas. He

The Nazis wanted the colonies back, and Uncle Ilyas wanted the Germans back, so he appeared on their marches carrying the schutztruppe flag and on platforms singing Nazi songs. So while you were grieving for him here, Ilyas said, Uncle Ilyas was dancing and singing in German cities and waving the schutztruppe flag in marches demanding the return of the colonies. Lebensraum did not only mean the Ukraine and Poland to them. The Nazi dream also included the hills and valleys and plains at the foot

The Nazis wanted the colonies back, and Uncle Ilyas wanted the Germans back, so he appeared on their marches carrying the schutztruppe flag and on platforms singing Nazi songs. So while you were grieving for him here, Ilyas said, Uncle Ilyas was dancing and singing in German cities and waving the schutztruppe flag in marches demanding the return of the colonies. Lebensraum did not only mean the Ukraine and Poland to them. The Nazi dream also included the hills and valleys and plains at the foot of that snow-capped mountain in Africa.

Uncle Ilyas was sent to Sachsenhausen concentration camp outside Berlin and his one surviving son, who was called Paul after the General in the Ostafrika war, voluntarily followed him there. It is not known what happened to his wife. Both Uncle Ilyas and his son Paul died in Sachsenhausen in 1942. The cause of Uncle Ilyas’s death is not recorded but from the memoir of an inmate who survived, it is known that the son of the black singer who voluntarily entered the camp to be with his father was shot trying to escape. So what we can know for sure, Ilyas told his parents, is that someone loved Uncle Ilyas enough to follow him to certain death in a concentration camp in order to keep him company.

By The Sea